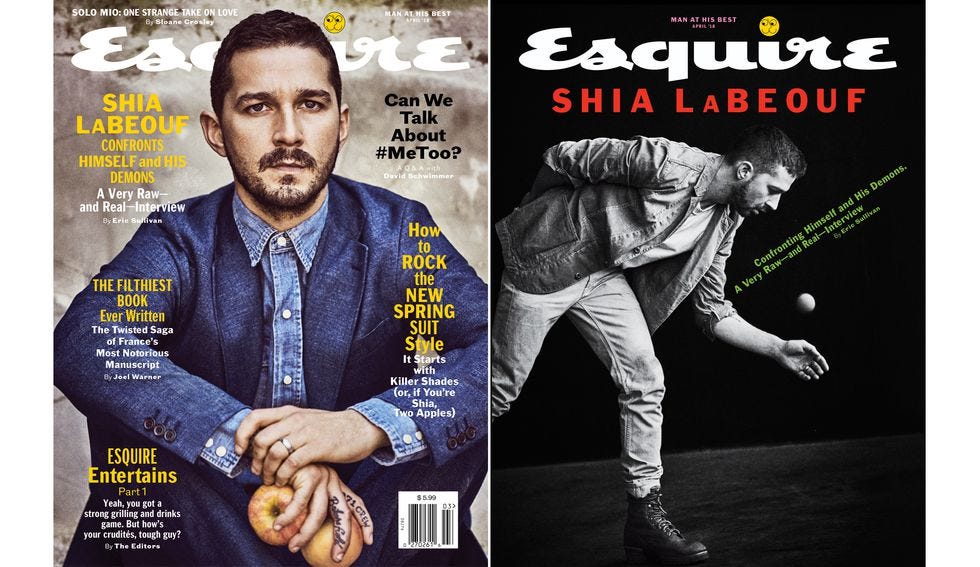

Shia LaBeouf is nervous about this story—“I have so much fear about this thing,” he confesses to me when we first meet—and it drives him to do what he’s always done when faced with something he cannot fully control: Prepare. Obsessively. For the past two months, he’s conducted practice interviews over the phone with his therapist, anticipating all of the possible scenarios, workshopping his responses to my questions. It’s been a long time since Vanity Fair put him on the cover of its August 2007 issue, wearing a spacesuit over a suit-suit (it looks as awkward as it sounds), and heralded him at age twenty-one as “the Next Tom Hanks.” More than a decade on, LaBeouf’s arc is less a stratospheric ascent than a misguided rocket wobbling across the sky, strewing wreckage.

Yes, LaBeouf is the guy who was handed a golden ticket and promptly lit it on fire. But too often we forget that everyone screws up on their path toward becoming an adult; and that few do so under the gaze of the public eye; and that by embracing the kind of capital-A Acting LaBeouf aims to do, we nourish the same spark from which his bad behavior stems. Tom Hardy, who worked with LaBeouf on 2012’s Lawless, points to the paradox central to their work. “A performer is asked to do two things,” he tells me. “To be disciplined and accountable, communicative and a pleasure to work with. And then, within a split second, they’re asked to be a psychopath. Authentically. It takes a very strong human being to sustain a genuine sense of well-being through that baptism of fire.” Then: “Drama is not known to attract stable types.”

LaBeouf invites me to dinner at a family-friendly joint in Sherman Oaks, the affluent Los Angeles neighborhood where he’s lived for nearly a decade. We are about ten miles southwest of Tujunga, where he lived from ages five to thirteen, when he became a full-time actor. He picked this spot because, as I learn, it’s a safe space, turf where he feels secure. He usually comes here with his wife, the actress and model Mia Goth, or his mother, Shayna, with whom he speaks daily.

When I arrive, I see LaBeouf through the window. He is alone at a four-top, his eyes trained forward, unmoving. As I approach him, he stands to greet me. His outfit is Valley Dad: well-fitted if unassuming khakis and a sweatshirt.

LaBeouf is here to discuss his new movie, Borg vs. McEnroe (April 13), though, as he says, “I’m a terrible used-car salesman.” To wit: “I have no interest in tennis. Zero. I only hate it more since having done this film. It’s an elitist sport.” As his voice tap-dances up and down the lower register, he speaks honestly and without hesitation. He plays John McEnroe, the tennis savant whose reputation as a powder keg often overshadowed his prodigious talent, with entropic physicality—fiery eyes, a fast smile, loose limbs ball-socketed to his trunk—but also with restraint: a born fighter who’s striving for self-control.

Unlike McEnroe’s outbursts, which became crowd-pleasing shtick, LaBeouf’s have left his offscreen reputation tattered. “McEnroe was a master at his rage,” he says. “I’m a buffoon. My public outbursts are failures. They’re not strategic. They’re a struggling motherfucker showing his ass in front of the world.” And since LaBeouf, more than anyone else, did the ripping, he knows it’s now on him to do the mending. “I’ve got to look at my failures in the face for a while,” he says. “I need to take ownership of my shit and clean up my side of the street a bit before I can go out there and work again, so I’m trying to stay creative and learn from my mistakes. I’ve been falling forward for a long time. Most of my life. The truth is, in my desperation, I lost the plot.” He pauses, then, as if to head off any potential awkwardness, says, “I know this is uncomfortable for you to bring up, bro. I get it. Just get to it.”

With LaBeouf, thirty-one, there’s not just one “it”; there is a truckload that has turned him into a walking meme. In the last year alone, he was stalked by Internet trolls; sued for $5 million by an L.A. bartender for a shouting match in a bowling alley; and arrested in Savannah for public intoxication. Footage of his booze-fueled, racially charged breakdown was leaked to the shame-generating machine that is TMZ, and he was sent to court-ordered rehab for ten weeks, starting last fall.

Given our hunger for celebrity schadenfreude, for which LaBeouf is manna, it’s easy to look past his electric talent and focus instead on his small mountain of baggage. But the genius is still there, still vibrant. I ask him if he thinks he’s performed the type of one-for-the-ages barn burner that even his fiercest critics would admit he, at his best, is capable of. He takes a sip of coffee—he’s now sober—looks out the window, and says, “Nah, not yet.” The real question is much tougher to answer: If LaBeouf’s instability informs his acting, will damping the one dim the other?

He says he is eager to be understood, but he also questions my intentions in a way that is less defensive than, well, on the offensive. “I know you have a job to do,” he says, leaning across the table, locking eyes. I ask what that is. “To continue this narrative that I’m a piece of shit.”

By the time that Vanity Fair cover came out, LaBeouf had already transcended lousy odds. The onetime star of Disney Channel’s Even Stevens had backflipped over the chasm into which most child actors tumble and landed at the feet of Steven Spielberg. The Hollywood kingpin had handpicked LaBeouf to be the face of the Transformers franchise, helmed by Michael Bay, and to play the son of—and potential successor to—Harrison Ford in 2008’s Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. By 2010, and for the second year in a row, Forbes deemed him Best Actor for the Buck. For every dollar he earned, the studio got an average of eighty-one dollars in return. He was bankable.

Audiences liked him as much as the studio execs did: He was funny, quick- witted, not distractingly handsome, and had a yes-ma’am charm that played well with the right target audiences. And the kid could act. If you take stock of Hollywood’s pileup of blockbuster blunders, the first Transformers holds up, and LaBeouf is one of its biggest selling points. Hardy says, “Shia has the ability to land scene after scene that builds a reality from utter fantasy. We know the robots aren’t really there. They just aren’t. When I watch Shia, they are.”

LaBeouf’s rise was all the more remarkable when you consider his less-than-Rockwellian childhood. His father, Jeffrey, grew up in San Francisco, trained as a commedia dell’arte clown, and once opened for the Doobie Brothers. He also served three tours in Vietnam and, once home, struggled for years with heroin addiction. Shayna, whom LaBeouf calls “my everything,” was raised on the Lower East Side of Manhattan and ran a head shop in the East Village before moving to California. To make money, she began selling barrettes, purses, and pins at a trade fair that moved up and down the coast. It was while she was in Los Angeles, peddling her wares at Echo Park, that she met Jeffrey, who was a born-again Christian teaching karate classes. They conceived their only child in a sleeping bag in the back of Jeffrey’s van. The boy’s name reflects his ethnicity—Jewish (from Shayna) and Cajun (from Jeffrey)—and loosely translates into “Thank God for the beef.”

The family lived in an apartment across from Echo Park, and Jeffrey would head there each day, a tricked-out hotel cart in tow, to sell hot dogs and snow cones and to perform as a clown. LaBeouf’s first acting experience was with his mom and dad, all three in costume, hawking wieners. Too often, Shayna and Jeffrey could get into massive fights. “They loved each other the most when they were creating together,” he says. “When they stopped creating, shit fell apart.” His parents separated when LaBeouf was three.

By the time LaBeouf was nine, things got worse. Their landlord, sick of all the sewing machines Shayna kept in their apartment, had kicked them out. They’d found a place in Tujunga, the biker-gang capital of the San Fernando Valley. Before Jeffrey left for a stint in rehab, he asked Dave, a biker who lived next door, to keep an eye on LaBeouf and his mother.

It didn’t help. One day, LaBeouf overheard a man raping his mother. “I froze,” he tells me, pausing. “The man ran out, and my mom ran after him. Dave came running over. I remember he had a crossbow.” By then, the rapist had fled. During a counseling session at the sheriff’s office, LaBeouf listened as his mother recounted her attacker’s appearance. “It was the first time I ever heard the word pubic,” he says. “That’s how she described his facial hair. The next day at school, I told some kid that his hair looked like pubic hair, and I remember getting in trouble. They never found the guy.

“When I got to rehab last year,” LaBeouf continues, “they said I had PTSD.” He says he now understands that the violence toward his mother that he witnessed, that he could not prevent, is the reason for his defensiveness, his own hair trigger for violence. “The first time I got arrested with a real charge, it stemmed from the same shit. Some guy bumped into my mother’s car with his car in a parking lot, and my head went right to ‘You need to avenge your mother!’ So I went after the dude with a knife.” (He didn’t use it.) It’s also why LaBeouf bought a gun as soon as he was able to; to this day, he sleeps with it. “I’ve always thought somebody was coming in. My whole life.”

Around the time of his mother’s attack, LaBeouf, then ten, went on a surf trip with Jeffrey to Malibu, where he met a kid about his age wearing the type of expensive outfit he could not afford. “I said, ‘What do you do?’” LaBeouf recalls. “He said he was an actor. That’s where it really started.” The kid told him he would never get past the first step: landing a modeling agent. “I was a weird- looking fucker,” LaBeouf says. Undeterred, he got crafty. “I looked up talent agents in the yellow pages. I put on this front like I was my own manager,” complete with a British lilt. One agent wasn’t fooled, but she was charmed, and LaBeouf was signed. He quickly began booking spots on ER, The X-Files, Freaks and Geeks, and Suddenly Susan.

His big break came in 2000: LaBeouf, then thirteen, landed the lead on Even Stevens. The show was a blast—“like going to Chuck E. Cheese,” he says. He was praised for his performance, which earned him a Daytime Emmy. To be closer to the set, he moved out of his mother’s place and for the next three years lived in a forty-dollar-a-night motel with Jeffrey, who’d completed rehab and become his son’s on-set guardian. LaBeouf says, “I was going to the Alano Club”—a twelve-step program—“with my dad. That was my daycare center. Then I’d go to work. That was my whole life.”

LaBeouf tells me that as part of his treatment last year, he underwent prolonged-exposure therapy, which is a fancy name for the counterintuitive process of poking at a wound until it stops bleeding. “You keep talking about it. You keep bringing it up, acting it out, thinking about its smell. Every which way you can get to it. And a lot of my shit has to do with my relationship with my dad,” he says. “That dude is my gasoline.” Whenever a scene required LaBeouf to conjure intense emotion, Jeffrey would stand next to the camera, just off set, so that LaBeouf could see him, focus on him. “I could work myself up into a frenzy,” he says. “He’s the whole reason I became an actor.”

LaBeouf poked at that paternal wound with a pen. Despite claiming not to be a good writer, he turned his thoughts into a screenplay, a full one, which he finished while still in rehab. The Black List, a site that tracks the most promising unproduced scripts in Hollywood, describes its plot as follows: “A child actor and his law-breaking, alcohol-abusing father attempt to mend their contentious relationship over the course of a decade.” LaBeouf listed a coauthor, Otis Lort, which he now admits is a pseudonym. He claims it’s of Cajun origin, but some cursory linguistic analysis suggests it is a combination of German and Danish that translates into “Wealthy Turd.” The film’s working title is the nickname Jeffrey has called his son for as long as LaBeouf can remember: Honey Boy.

The next day, LaBeouf tells me to meet him at Descanso Gardens, a tranquil refuge from the hustle of L.A. halfway between Echo Park and Tujunga. I arrive earlier than I did for dinner, but he still beats me to the mark. He’s seated on a bench at the entrance, tickets for both of us in one hand and a cup of coffee in the other, waiting for our scene to begin.

After dispensing with pleasantries, he once again questions my intentions. “I went to sleep last night thinking that this is going to be some boo-hoo piece: ‘Oh, here he is not trying to own his shit. He’s trying to put it on his father....’ My dad handed me a lot, and his legacy was an emotional one. And it wasn’t scarring. He handed me texture. My dad blessed me that way.” He’s wearing a shirt that brings him talismanic comfort, a blue oxford button- down from the set of a movie he made at the tail end of his adolescence, and it reminds him of the family created on set. He bought his hat, emblazoned with the Bavarian coat of arms, on a trip to Germany, and to make it his own, scribbled on it with marker.

Over the past couple of years, LaBeouf’s style, a mix of military, athleisure, and (mostly) normcore—what he calls “blue collar”—has become a fixation among men’s-wear enthusiasts. Kanye West, for one, is a fan: In a “No More Parties in L. A.” outtake, he raps, “I wish I dressed as fresh as Shia LaBeouf.” When Kanye went to LaBeouf’s house to discuss possible art collaborations, he asked if he could have some of his clothes for a pop-up shop. “Around the same time, I took my mother to his concert,” LaBeouf tells me. “She is, of course, obsessed with Kanye West. When I brought her backstage, he was a fucking sweetheart to her. And it just felt fair. So I’m like, ‘Go for it, my guy. Take everything you want.’ And he did. He took all my fucking clothes. Me and him haven’t really been in contact since he blew up onstage and, you know, shit on me.” (In November 2016, during a fifteen-minute midconcert meltdown in Sacramento, Kanye said, “Shia LaBeouf: Kid Cudi feels a way. Call him.” LaBeouf directed Cudi in a music video and a short film in 2011. What West meant is open to interpretation.) I ask if he’s tried to reach out. “Of course, bro. I fucking love Kanye West. He’s going through a lot. And I don’t know where he’s at or what he’s doing.” Last May, style bloggers worked themselves into a tizzy when Kanye was photographed wearing the exact same cap that LaBeouf had worn in public countless times before. “The dude has a lot of my shit,” he says. Yeezy even took his Indiana Jones hat.

LaBeouf prefers to wear clothing with personal history. It makes him feel safe. Like with places. As we stroll the property, he says, “This area is the money of the Valley. My family used to come here to dream. We’d be like, ‘Wouldn’t it be cool to one day own a tree?’ It has a calming promise.” He’ll take as much as he can get: With me, he’s entering what he considers a “very unsafe situation”: a dissection of his career’s descent.

By 2011, after the release of Transformers: Dark of the Moon—LaBeouf’s third and final entry in the franchise, for which he reportedly made $15 million—his films had grossed north of $4 billion. But he hadn’t found artistic satisfaction in his work since the first one. At the time, he says, he struggled to see the merit in what he was doing. When I ask him to elaborate, he says he doesn’t want to once again bite the hand that fed him so well: “Michael and Steven did a lot for me. I’m not going to pooh-pooh those dudes anymore.”

Then he does just that: “My hang-up with those films was that they felt irrelevant. They felt dated as fuck... You come up on these stories about Easy Rider and Raging Bull and De Niro and Scorsese and Hopper, and you find value in what they do. Meanwhile, you’re chasing energon crystals. It’s very hard to keep doing what you’re doing when you feel like it’s the antithesis of your purpose on this planet.” He was twenty-five years old, and says he already felt he was “living in a gilded cage. No one gives a fuck about your problems. Everybody’s like, ‘Hey, man, you’re riding the wave!’” For a time, he figured college offered an escape hatch, so he applied to Yale, bolstered by a letter of recommendation from Spielberg. He says he got in but decided not to go. He saved a copy of Spielberg’s letter. He keeps it in his safe.

Feeling trapped, LaBeouf reverted to the tried-and-true. “My way of running is to drink. I’m a good old-fashioned drunk—whiskey and beer—and have been since I touched alcohol.” In November 2007, he was arrested for trespassing at a Walgreens in Chicago. The next July, while driving late at night, he was struck by another car that ran a red light. His F-150 flipped, and he almost lost a finger. When the police arrived, he refused a Breathalyzer and was given a misdemeanor DUI. He still has the door from the truck; it leans against a wall in his house and he sees it every day. I ask him what it represents. “Failure,” he says. “Fallibility.”

Failure has always been what he uses to improve himself. While filming a scene with Josh Brolin in Oliver Stone’s Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps (2010) in which they have a tête-à-tête in the woods, he found himself outacted and overcompensating. “Insecure actors do too much,” LaBeouf says. “In that scene, I’m letting ambition get in the way of truth.” He calls this “one of my most traumatic experiences.” LaBeouf pledged to choose roles that were, as he says, “chasing sincerity,” like those taken by his heroes—Gary Oldman, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Joaquin Phoenix. He turned down offers to appear in The Social Network, 127 Hours, and The Bourne Legacy, and instead opted for characters who were, like him, young men in existential crisis.

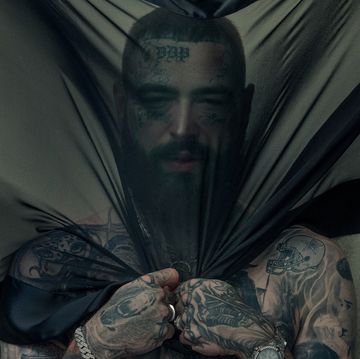

He dove headfirst into the deep end of character prep, blurring the line between acting and reality. While filming Lawless, he drank moonshine by the gallon, carved a message from his character into the door of Mia Wasikowska’s hotel room, and knocked out Tom Hardy. On the set of 2013’s Charlie Countryman, he dropped acid and choked the director when he tried to break for lunch. That year, during rehearsals for the Broadway production of Orphans, meant to be his first foray into stage acting, he became so enraged that Alec Baldwin had not prepped as much as he had that LaBeouf openly antagonized him and was fired. Unable to give up on the character, LaBeouf started following his ex-costar home from the theater. Baldwin later told New York magazine, “LaBeouf seems to carry with him, to put it mildly, a jailhouse mentality.” He wrote Baldwin an apology and then posted it on Twitter. It didn’t take long for online sleuths to discover that nearly every word had been plagiarized from an essay called “What Is a Man?” written by Tom Chiarella and published in the pages of this magazine. (There are several examples of LaBeouf’s plagiarism but only one that involves Esquire.)

But his dedication sometimes paid off, and for all parties involved. In 2014’s Fury, LaBeouf plays a devout gunner in a tank crew during the final days of World War II. To prepare, he embedded with the National Guard and became a chaplain’s assistant. To mimic the result of a smack to the face from the recoil of a gun, a common injury for gunners at the time, he had a dentist in the Valley shave down his lower incisor below the gum line. He sliced two parallel inch-long scars on his right cheek and, to keep them fresh, reopened them as needed for the duration of the seventy-day shoot, says director David Ayer. “He shows up and he has this scratch on his face, saying he needed to do this. And I’m like, ‘You know, we have makeup people that can do that stuff.’ But it was his ritual, part of putting on his acting armor. And when you have someone who’s really going for it, it breathes through the cast. Everyone else steps up.”

LaBeouf was no longer blurring that line between acting and reality; he was ignoring it altogether. In February 2014, before Fury was released, he walked the red carpet at the Berlin International Film Festival wearing a paper bag on his head that read, “I am not famous anymore.” It appeared as though acting—or perhaps its abandonment, but definitely not reality—had won out.

It’s hard to avoid the impression that LaBeouf, once a sure thing in Hollywood, has now successfully marginalized himself.

Studios are wary of hiring an actor who’s a live wire on set and a risk during press junkets, where he might renounce the projects he was meant to promote. “I’m run out,” he tells me. “No one’s giving me a shot right now. Spike Lee is making a movie. I was talking to him about it. He goes to the money and pushes to try to get me in the movie, the money says no, and that’s the end of me hanging out with Spike Lee for this film.”

Yet as LaBeouf has veered toward smaller, more auteur-driven movies, his work has only gotten better. His performance as the rat-tailed spirit animal of a team of nomadic door-to-door magazine salespeople in 2016’s American Honey garnered some of the best reviews of his career. As a Marine with PTSD in Dito Montiel’s Man Down, his most recent theatrical release, LaBeouf is phenomenal; the problem is everything else. Reports of its poor performance at the one theater where it opened in the UK—fewer than a dozen tickets were sold—were spun as a sign of LaBeouf’s dimming star power.

As he’s dropped off the moviegoing public’s radar, he’s appeared on another. For more than a year, he’s been under sustained attack by trolls from the /pol/ thread on 4chan, the anything-goes message board that attracts disaffected men who love to skewer political correctness. On the day of Trump’s inauguration, LaBeouf and two artists—Luke Turner, a Brit, and Nastja Säde Rönkkö, a Finn, with whom he’s collaborated on a series of performance-art projects—launched a piece at the Museum of the Moving Image, in Queens, called #HEWILLNOTDIVIDEUS. The idea was both simplistic and endearing: Participants were encouraged to walk up to a camera on the museum’s outer wall, live-streamed 24/7 and for the duration of Trump’s time in office, and say, “He will not divide us.” But you could also say whatever you wanted. And 4chan trolls showed up each day, salivating. A few donned SS garb and heiled Hitler. For LaBeouf, glorifying Nazis was a step too far. After a series of clashes, one of which led to LaBeouf’s arrest (no charges were pressed), the museum closed down the exhibit. #HWNDU was then installed, trolled, and subsequently removed from a theater in Albuquerque, a field in Tennessee, and an art center in Liverpool. Since October, it has been housed at an arts center in Nantes, France’s sixth-largest city.

“I get that it’s fun to beat up on the millionaire celebrity,” LaBeouf says. He even allows that “there’s a level of what 4chan did that’s brilliant.” But since he was the target, he thinks, most people overlooked the fact that real extremists may have committed real crimes. He’s not wrong: The vandalism on the property in Tennessee didn’t get much attention until LaBeouf and his collaborators published the results of their own investigation. As far as the trolls were concerned, they’d found a surefire way to crap on the pet project of a famous actor and provoke his response.

They had reason to think that would work. Borg vs. McEnroe director Janus Metz points out the trait in LaBeouf—“Shia tries to break down the barrier between acting and reality”—that has been a boon for his craft but a burden when dealing with being a regular dude. Since last July’s arrest in Georgia, however, LaBeouf says his priorities have shifted paradigmatically. “For a long time, I thought that life was secondary to art,” he says. “And then you realize you can’t have this art thing without the life thing. I’m just trying to deal with my life right now, ’cause I don’t have fuck-all to offer the world until I do.”

We’ve walked Descanso’s manicured grounds, through sun-sprinkled oak groves and rows of lilac shrubs. We sit down on a weathered wood bench beneath a crab-apple tree. LaBeouf is ready to talk about what happened in Savannah.

It started at 4:00 a.m. on a Saturday. A drunk LaBeouf asked to bum a smoke from two pedestrians, one of whom was a police officer. He was denied. He ignored the officer’s warnings to calm down, and was handcuffed and brought to the station. TMZ obtained Savannah police footage. Lots of it: Shia being cuffed, in the back of the police car, getting processed, each clip ickier and more damning than the last. In one, he brags about his “millionaire lawyers.” In another, he belittles a black officer for being “stuck in a police force that doesn’t give a fuck ’bout you. So you want to arrest, what, white people who give a fuck?” He suggests that a white officer’s wife watches porn involving “licking a black dick,” continuing with “Don’t you feel like, ‘Fuck, man, I ain’t got all the goods?’” One can lose track of the number of times he calls various officers “bitch” and “whore.”

When I ask LaBeouf about that night, his answer comes in fits and starts. “What went on in Georgia was mortifying. White privilege and desperation and disaster... It came from a place of self-centered delusion... It was me trying to absolve myself of guilt for getting arrested.” And finally, “I fucked up.”

He was in Savannah to film The Peanut Butter Falcon, a buddy adventure about a developmentally disabled man who escapes from his nursing home to pursue his dream of becoming a pro wrestler. The role is played by the man for whom the script was written: Zachary Gottsagen, a thirty-two-year-old actor with Down syndrome from Boynton Beach, Florida. After viewing a clip of Gottsagen acting out some of the scenes, LaBeouf committed to the role of a crab fisherman who helps the wrestler- to-be on his journey. “It just hit me over the head,” he says. “I was like, ‘Holy moly, this is the new adventure.’ I knew it was yes before I even read the script.” On set, he and Gottsagen bonded instantly. “We picked Shia up in a ’74 Ford Ranger,” says Michael Schwartz, who codirected the film with Tyler Nilson. “He got in the back with Zack and we drove an hour down the coast. Shia was asking Zack questions: ‘Who do you love? Where do you come from? What makes you happy?’” Nilson adds, “Zack wanted to know if Shia could film some more episodes of Even Stevens.” But Gottsagen tells me that when he found out about LaBeouf’s arrest, “I was angry. Mad. Frustrated. I didn’t want to work with Shia anymore.”

The morning he got out of jail, LaBeouf attended a small party for the cast and crew, and no one brought up what had happened. “Everybody was pussyfooting around it,” he says. As soon as Gottsagen arrived, he beelined for LaBeouf and sat on the floor, and there LaBeouf joined him. They talked for twenty minutes. Gottsagen told him, “You’re already famous. This is my chance. And you’re ruining it.”

“To hear him say that he was disappointed in me probably changed the course of my life,” LaBeouf says. “ ’Cause I was still fighting. I was still on my ‘Look how fast they released the videos! They don’t release these!’ Just on my defense-mechanism-fear garbage. And you can’t do that to him. He keeps it one thousand with you, and that shit doesn’t even make sense to him. Zack can’t not shoot straight, and bless him for it, ’cause in that moment, I needed a straight shooter who I couldn’t argue with.” He says their conversation continued on set: “We were getting ready to do a scene and Zack said, ‘Do you believe in God?’ And I thought, No fuckin’ way are you about to explain God to me, Zack.” LaBeouf tries to keep it together. His voice jumps an octave. “Zack said, ‘Even if He’s not real, what does it hurt?’” He turns his face away. He takes a breath and continues.

“I don’t believe in God... But did I see God? Did I hear God? Through Zack, yeah. He met me with love, and at the time, love was truth, and he didn’t pull punches. And I’m grateful, not even on some cheeseball shit trying to sell a movie. In real life. That motherfucker is magical.” LaBeouf’s posture is all right angles, as if the memory alone has straightened him. “Zack allowed me to be open to help when it came.”

When LaBeouf first checked into rehab, he was asked about the pop—the moment your head gets pulled out of your ass and clarity washes over you. “For me,” he says, “it was Zack.” LaBeouf is not broken but on the other side of brokenness, and he’s looked back at the wreckage for long enough. It’s time to go home. He rises, puts his hands in his pockets, and walks out from under the shade of the crab-apple tree.